Evaluate documentation

Considerations for model evaluation

Considerations for model evaluation

Developing an ML model is rarely a one-shot deal: it often involves multiple stages of defining the model architecture and tuning hyper-parameters before converging on a final set. Responsible model evaluation is a key part of this process, and 🤗 Evaluate is here to help!

Here are some things to keep in mind when evaluating your model using the 🤗 Evaluate library:

Properly splitting your data

Good evaluation generally requires three splits of your dataset:

- train: this is used for training your model.

- validation: this is used for validating the model hyperparameters.

- test: this is used for evaluating your model.

Many of the datasets on the 🤗 Hub are separated into 2 splits: train and validation; others are split into 3 splits (train, validation and test) — make sure to use the right split for the right purpose!

Some datasets on the 🤗 Hub are already separated into these three splits. However, there are also many that only have a train/validation or only train split.

If the dataset you’re using doesn’t have a predefined train-test split, it is up to you to define which part of the dataset you want to use for training your model and which you want to use for hyperparameter tuning or final evaluation.

Depending on the size of the dataset, you can keep anywhere from 10-30% for evaluation and the rest for training, while aiming to set up the test set to reflect the production data as close as possible. Check out this thread for a more in-depth discussion of dataset splitting!

The impact of class imbalance

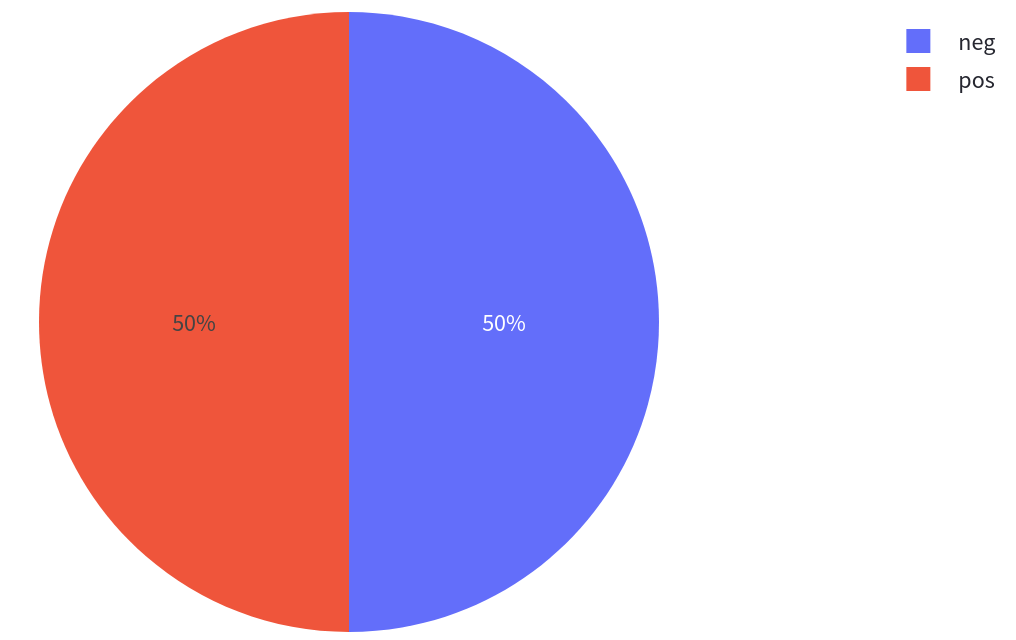

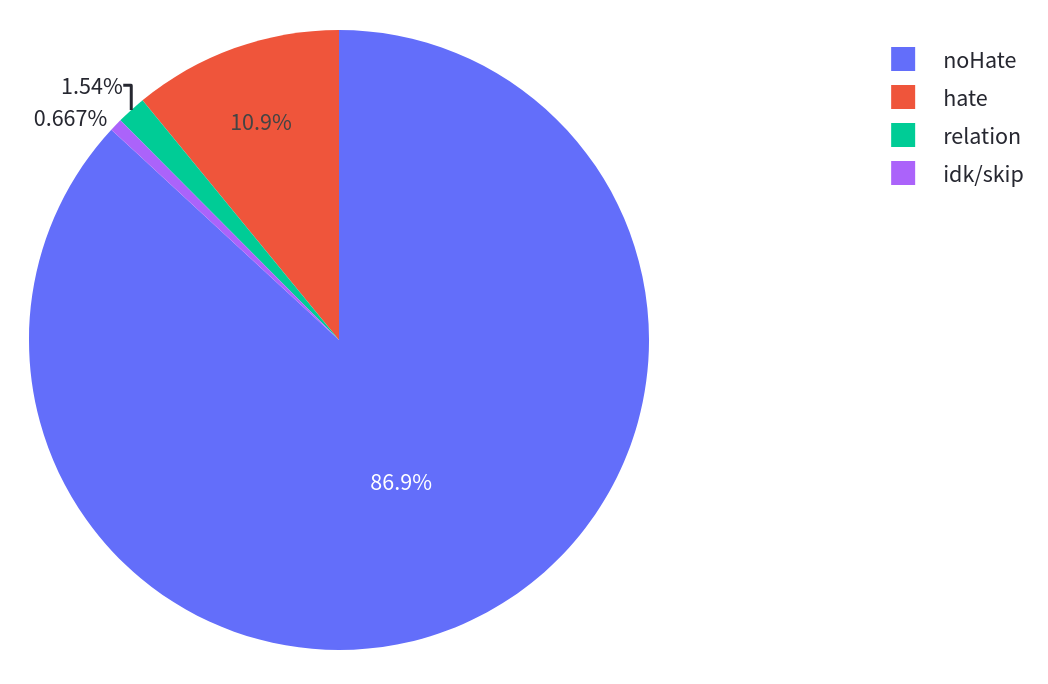

While many academic datasets, such as the IMDb dataset of movie reviews, are perfectly balanced, most real-world datasets are not. In machine learning a balanced dataset corresponds to a datasets where all labels are represented equally. In the case of the IMDb dataset this means that there are as many positive as negative reviews in the dataset. In an imbalanced dataset this is not the case: in fraud detection for example there are usually many more non-fraud cases than fraud cases in the dataset.

Having an imbalanced dataset can skew the results of your metrics. Imagine a dataset with 99 “non-fraud” cases and 1 “fraud” case. A simple model that always predicts “non-fraud” cases would give yield a 99% accuracy which might sound good at first until you realize that you will never catch a fraud case.

Often, using more than one metric can help get a better idea of your model’s performance from different points of view. For instance, metrics like recall and precision can be used together, and the f1 score is actually the harmonic mean of the two.

In cases where a dataset is balanced, using accuracy can reflect the overall model performance:

In cases where there is an imbalance, using F1 score can be a better representation of performance, given that it encompasses both precision and recall.

Using accuracy in an imbalanced setting is less ideal, since it is not sensitive to minority classes and will not faithfully reflect model performance on them.

Offline vs. online model evaluation

There are multiple ways to evaluate models, and an important distinction is offline versus online evaluation:

Offline evaluation is done before deploying a model or using insights generated from a model, using static datasets and metrics.

Online evaluation means evaluating how a model is performing after deployment and during its use in production.

These two types of evaluation can use different metrics and measure different aspects of model performance. For example, offline evaluation can compare a model to other models based on their performance on common benchmarks, whereas online evaluation will evaluate aspects such as latency and accuracy of the model based on production data (for example, the number of user queries that it was able to address).

Trade-offs in model evaluation

When evaluating models in practice, there are often trade-offs that have to be made between different aspects of model performance: for instance, choosing a model that is slightly less accurate but that has a faster inference time, compared to a high-accuracy that has a higher memory footprint and requires access to more GPUs.

Here are other aspects of model performance to consider during evaluation:

Interpretability

When evaluating models, interpretability (i.e. the ability to interpret results) can be very important, especially when deploying models in production.

For instance, metrics such as exact match have a set range (between 0 and 1, or 0% and 100%) and are easily understandable to users: for a pair of strings, the exact match score is 1 if the two strings are the exact same, and 0 otherwise.

Other metrics, such as BLEU are harder to interpret: while they also range between 0 and 1, they can vary greatly depending on which parameters are used to generate the scores, especially when different tokenization and normalization techniques are used (see the metric card for more information about BLEU limitations). This means that it is difficult to interpret a BLEU score without having more information about the procedure used for obtaining it.

Interpretability can be more or less important depending on the evaluation use case, but it is a useful aspect of model evaluation to keep in mind, since communicating and comparing model evaluations is an important part of responsible machine learning.

Inference speed and memory footprint

While recent years have seen increasingly large ML models achieve high performance on a large variety of tasks and benchmarks, deploying these multi-billion parameter models in practice can be a challenge in itself, and many organizations lack the resources for this. This is why considering the inference speed and memory footprint of models is important, especially when doing online model evaluation.

Inference speed refers to the time that it takes for a model to make a prediction — this will vary depending on the hardware used and the way in which models are queried, e.g. in real time via an API or in batch jobs that run once a day.

Memory footprint refers to the size of the model weights and how much hardware memory they occupy. If a model is too large to fit on a single GPU or CPU, then it has to be split over multiple ones, which can be more or less difficult depending on the model architecture and the deployment method.

When doing online model evaluation, there is often a trade-off to be done between inference speed and accuracy or precision, whereas this is less the case for offline evaluation.

Limitations and bias

All models and all metrics have their limitations and biases, which depend on the way in which they were trained, the data that was used, and their intended uses. It is important to measure and communicate these limitations clearly to prevent misuse and unintended impacts, for instance via model cards which document the training and evaluation process.

Measuring biases can be done by evaluating models on datasets such as Wino Bias or MD Gender Bias, and by doing Interactive Error Analyis to try to identify which subsets of the evaluation dataset a model performs poorly on.

We are currently working on additional measurements that can be used to quantify different dimensions of bias in both models and datasets — stay tuned for more documentation on this topic!