Huggy Lingo: Using Machine Learning to Improve Language Metadata on the Hugging Face Hub

Huggy Lingo: Using Machine Learning to Improve Language Metadata on the Hugging Face Hub

tl;dr: We're using machine learning to detect the language of Hub datasets with no language metadata, and librarian-bots to make pull requests to add this metadata.

The Hugging Face Hub has become the repository where the community shares machine learning models, datasets, and applications. As the number of datasets grows, metadata becomes increasingly important as a tool for finding the right resource for your use case.

In this blog post, I'm excited to share some early experiments which seek to use machine learning to improve the metadata for datasets hosted on the Hugging Face Hub.

Language Metadata for Datasets on the Hub

There are currently ~50K public datasets on the Hugging Face Hub. Metadata about the language used in a dataset can be specified using a YAML field at the top of the dataset card.

All public datasets specify 1,716 unique languages via a language tag in their metadata. Note that some of them will be the result of languages being specified in different ways i.e. en vs eng vs english vs English.

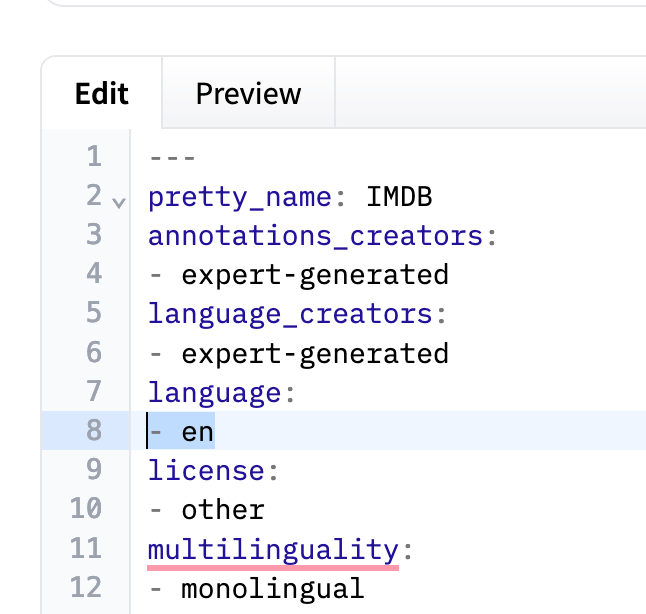

For example, the IMDB dataset specifies en in the YAML metadata (indicating English):

Section of the YAML metadata for the IMDB dataset

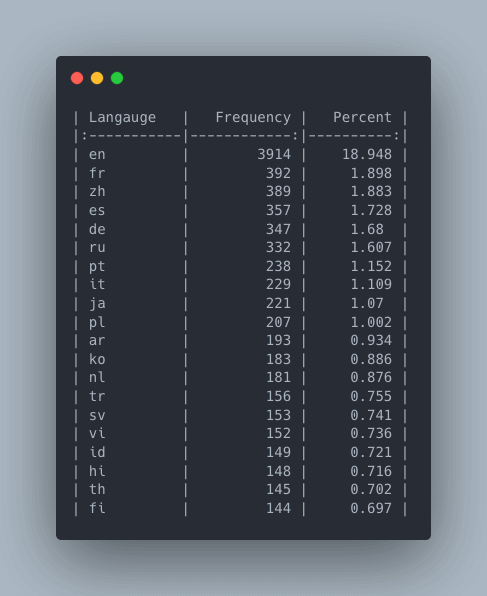

It is perhaps unsurprising that English is by far the most common language for datasets on the Hub, with around 19% of datasets on the Hub listing their language as en (not including any variations of en, so the actual percentage is likely much higher).

The frequency and percentage frequency for datasets on the Hugging Face Hub

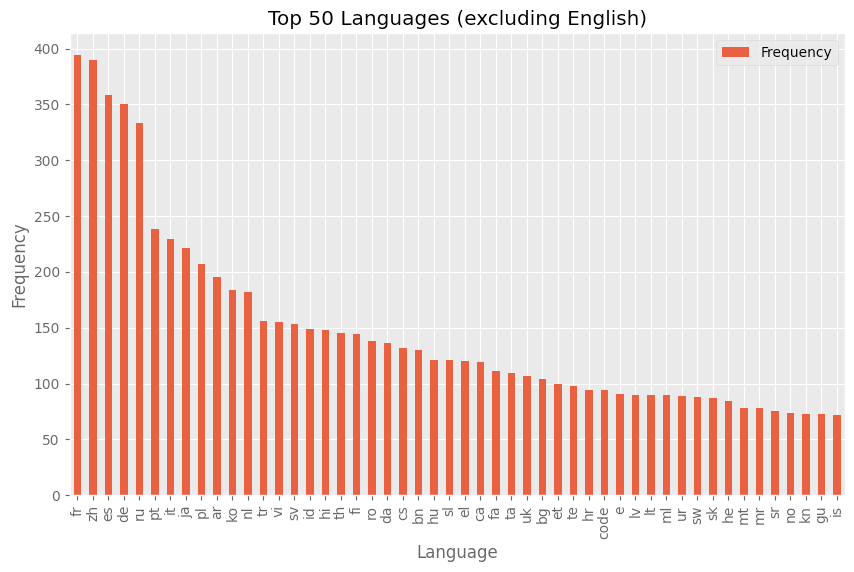

What does the distribution of languages look like if we exclude English? We can see that there is a grouping of a few dominant languages and after that there is a pretty smooth fall in the frequencies at which languages appear.

Distribution of language tags for datasets on the hub excluding English.

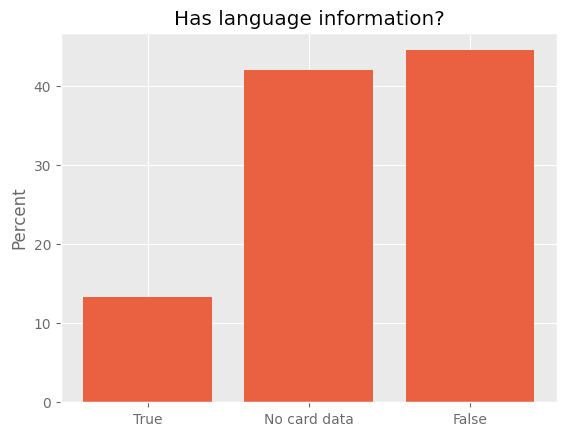

However, there is a major caveat to this. Most datasets (around 87%) do not specify the language used; only approximately 13% of datasets include language information in their metadata.

The percent of datasets which have language metadata. True indicates language metadata is specified, False means no language data is listed. No card data means that there isn't any metadata or it couldn't be loaded by the `huggingface_hub` Python library.

Why is Language Metadata Important?

Language metadata can be a vital tool for finding relevant datasets. The Hugging Face Hub allows you to filter datasets by language. For example, if we want to find datasets with Dutch language we can use a filter on the Hub to include only datasets with Dutch data.

Currently this filter returns 184 datasets. However, there are datasets on the Hub which include Dutch but don't specify this in the metadata. These datasets become more difficult to find, particularly as the number of datasets on the Hub grows.

Many people want to be able to find datasets for a particular language. One of the major barriers to training good open source LLMs for a particular language is a lack of high quality training data.

If we switch to the task of finding relevant machine learning models, knowing what languages were included in the training data for a model can help us find models for the language we are interested in. This relies on the dataset specifying this information.

Finally, knowing what languages are represented on the Hub (and which are not), helps us understand the language biases of the Hub and helps inform community efforts to address gaps in particular languages.

Predicting the Languages of Datasets Using Machine Learning

We’ve already seen that many of the datasets on the Hugging Face Hub haven’t included metadata for the language used. However, since these datasets are already shared openly, perhaps we can look at the dataset and try to identify the language using machine learning.

Getting the Data

One way we could access some examples from a dataset is by using the datasets library to download the datasets i.e.

from datasets import load_dataset

dataset = load_dataset("biglam/on_the_books")

However, for some of the datasets on the Hub, we might be keen not to download the whole dataset. We could instead try to load a sample of the dataset. However, depending on how the dataset was created, we might still end up downloading more data than we’d need onto the machine we’re working on.

Luckily, many datasets on the Hub are available via the dataset viewer API. It allows us to access datasets hosted on the Hub without downloading the dataset locally. The API powers the dataset viewer you will see for many datasets hosted on the Hub.

For this first experiment with predicting language for datasets, we define a list of column names and data types likely to contain textual content i.e. text or prompt column names and string features are likely to be relevant image is not. This means we can avoid predicting the language for datasets where language information is less relevant, for example, image classification datasets. We use the dataset viewer API to get 20 rows of text data to pass to a machine learning model (we could modify this to take more or fewer examples from the dataset).

This approach means that for the majority of datasets on the Hub we can quickly request the contents of likely text columns for the first 20 rows in a dataset.

Predicting the Language of a Dataset

Once we have some examples of text from a dataset, we need to predict the language. There are various options here, but for this work, we used the facebook/fasttext-language-identification fastText model created by Meta as part of the No Language Left Behind work. This model can detect 217 languages which will likely represent the majority of languages for datasets hosted on the Hub.

We pass 20 examples to the model representing rows from a dataset. This results in 20 individual language predictions (one per row) for each dataset.

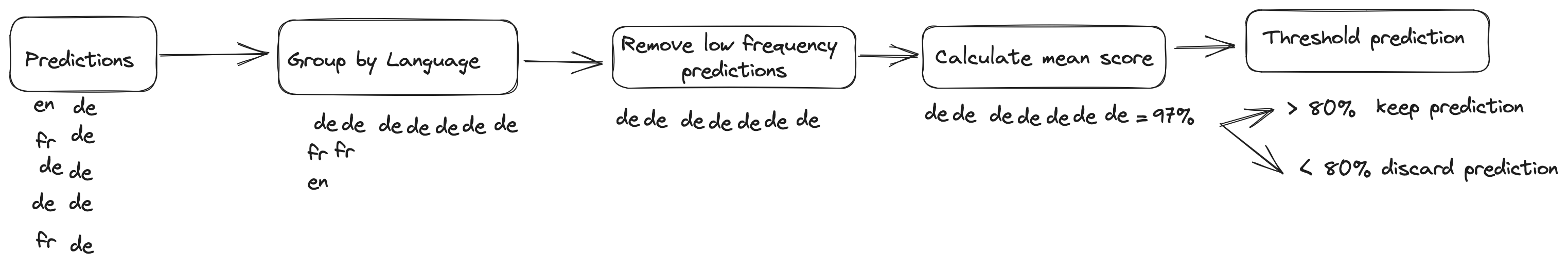

Once we have these predictions, we do some additional filtering to determine if we will accept the predictions as a metadata suggestion. This roughly consists of:

- Grouping the predictions for each dataset by language: some datasets return predictions for multiple languages. We group these predictions by the language predicted i.e. if a dataset returns predictions for English and Dutch, we group the English and Dutch predictions together.

- For datasets with multiple languages predicted, we count how many predictions we have for each language. If a language is predicted less than 20% of the time, we discard this prediction. i.e. if we have 18 predictions for English and only 2 for Dutch we discard the Dutch predictions.

- We calculate the mean score for all predictions for a language. If the mean score associated with a languages prediction is below 80% we discard this prediction.

Diagram showing how predictions are handled.

Once we’ve done this filtering, we have a further step of deciding how to use these predictions. The fastText language prediction model returns predictions as an ISO 639-3 code (an international standard for language codes) along with a script type. i.e. kor_Hang is the ISO 693-3 language code for Korean (kor) + Hangul script (Hang) a ISO 15924 code representing the script of a language.

We discard the script information since this isn't currently captured consistently as metadata on the Hub and, where possible, we convert the language prediction returned by the model from ISO 639-3 to ISO 639-1 language codes. This is largely done because these language codes have better support in the Hub UI for navigating datasets.

For some ISO 639-3 codes, there is no ISO 639-1 equivalent. For these cases we manually specify a mapping if we deem it to make sense, for example Standard Arabic (arb) is mapped to Arabic (ar). Where an obvious mapping is not possible, we currently don't suggest metadata for this dataset. In future iterations of this work we may take a different approach. It is important to recognise this approach does come with downsides, since it reduces the diversity of languages which might be suggested and also relies on subjective judgments about what languages can be mapped to others.

But the process doesn't stop here. After all, what use is predicting the language of the datasets if we can't share that information with the rest of the community?

Using Librarian-Bot to Update Metadata

To ensure this valuable language metadata is incorporated back into the Hub, we turn to Librarian-Bot! Librarian-Bot takes the language predictions generated by Meta's facebook/fasttext-language-identification fastText model and opens pull requests to add this information to the metadata of each respective dataset.

This system not only updates the datasets with language information, but also does it swiftly and efficiently, without requiring manual work from humans. If the owner of a repo decided to approve and merge the pull request, then the language metadata becomes available for all users, significantly enhancing the usability of the Hugging Face Hub. You can keep track of what the librarian-bot is doing here!

Next Steps

As the number of datasets on the Hub grows, metadata becomes increasingly important. Language metadata, in particular, can be incredibly valuable for identifying the correct dataset for your use case.

With the assistance of the dataset viewer API and the Librarian-Bots, we can update our dataset metadata at a scale that wouldn't be possible manually. As a result, we're enriching the Hub and making it an even more powerful tool for data scientists, linguists, and AI enthusiasts around the world.

As the machine learning librarian at Hugging Face, I continue exploring opportunities for automatic metadata enrichment for machine learning artefacts hosted on the Hub. Feel free to reach out (daniel at thiswebsite dot co) if you have ideas or want to collaborate on this effort!