Audio Course documentation

Unit 3. Transformer architectures for audio

Unit 3. Transformer architectures for audio

In this course we will primarily consider transformer models and how they can be applied to audio tasks. While you don’t need to know the inner details of these models, it’s useful to understand the main concepts that make them work, so here’s a quick refresher. For a deep dive into transformers, check out our LLM Course.

How does a transformer work?

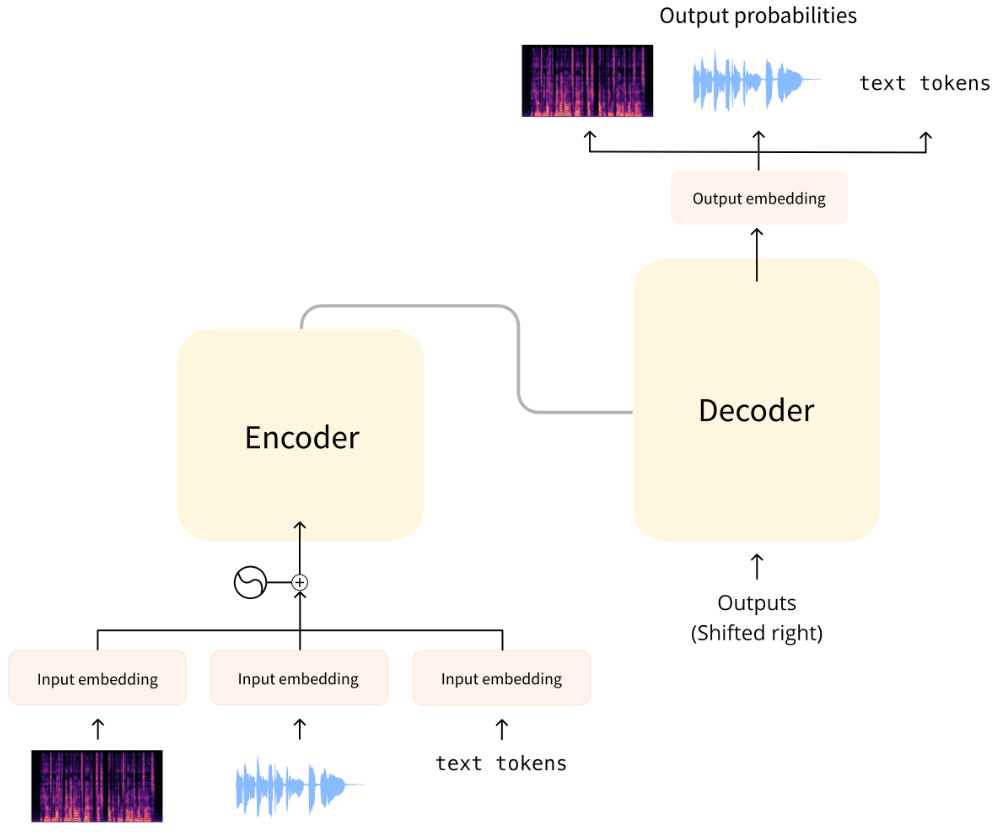

The original transformer model was designed to translate written text from one language into another. Its architecture looked like this:

On the left is the encoder and on the right is the decoder.

The encoder receives an input, in this case a sequence of text tokens, and builds a representation of it (its features). This part of the model is trained to acquire understanding from the input.

The decoder uses the encoder’s representation (the features) along with other inputs (the previously predicted tokens) to generate a target sequence. This part of the model is trained to generate outputs. In the original design, the output sequence consisted of text tokens.

There are also transformer-based models that only use the encoder part (good for tasks that require understanding of the input, such as classification), or only the decoder part (good for tasks such as text generation). An example of an encoder-only model is BERT; an example of a decoder-only model is GPT2.

A key feature of transformer models is that they are built with special layers called attention layers. These layers tell the model to pay specific attention to certain elements in the input sequence and ignore others when computing the feature representations.

Using transformers for audio

The audio models we’ll cover in this course typically have a standard transformer architecture as shown above, but with a slight modification on the input or output side to allow for audio data instead of text. Since all these models are transformers at heart, they will have most of their architecture in common and the main differences are in how they are trained and used.

For audio tasks, the input and/or output sequences may be audio instead of text:

Automatic speech recognition (ASR): The input is speech, the output is text.

Speech synthesis (TTS): The input is text, the output is speech.

Audio classification: The input is audio, the output is a class probability — one for each element in the sequence or a single class probability for the entire sequence.

Voice conversion or speech enhancement: Both the input and output are audio.

There are a few different ways to handle audio so it can be used with a transformer. The main consideration is whether to use the audio in its raw form — as a waveform — or to process it as a spectrogram instead.

Model inputs

The input to an audio model can be either text or sound. The goal is to convert this input into an embedding vector that can be processed by the transformer architecture.

Text input

A text-to-speech model takes text as input. This works just like the original transformer or any other NLP model: The input text is first tokenized, giving a sequence of text tokens. This sequence is sent through an input embedding layer to convert the tokens into 512-dimensional vectors. Those embedding vectors are then passed into the transformer encoder.

Waveform input

An automatic speech recognition model takes audio as input. To be able to use a transformer for ASR, we first need to convert the audio into a sequence of embedding vectors somehow.

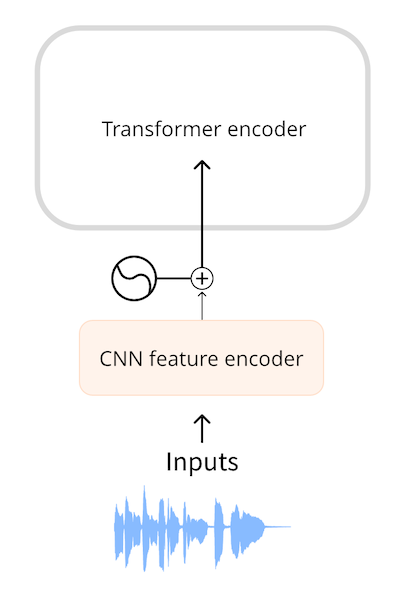

Models such as Wav2Vec2 and HuBERT use the audio waveform directly as the input to the model. As you’ve seen in the chapter on audio data, a waveform is a one-dimensional sequence of floating-point numbers, where each number represents the sampled amplitude at a given time. This raw waveform is first normalized to zero mean and unit variance, which helps to standardize audio samples across different volumes (amplitudes).

After normalizing, the sequence of audio samples is turned into an embedding using a small convolutional neural network, known as the feature encoder. Each of the convolutional layers in this network processes the input sequence, subsampling the audio to reduce the sequence length, until the final convolutional layer outputs a 512-dimensional vector with the embedding for each 25 ms of audio. Once the input sequence has been transformed into a sequence of such embeddings, the transformer will process the data as usual.

Spectrogram input

One downside of using the raw waveform as input is that they tend to have long sequence lengths. For example, thirty seconds of audio at a sampling rate of 16 kHz gives an input of length 30 * 16000 = 480000. Longer sequence lengths require more computations in the transformer model, and so higher memory usage.

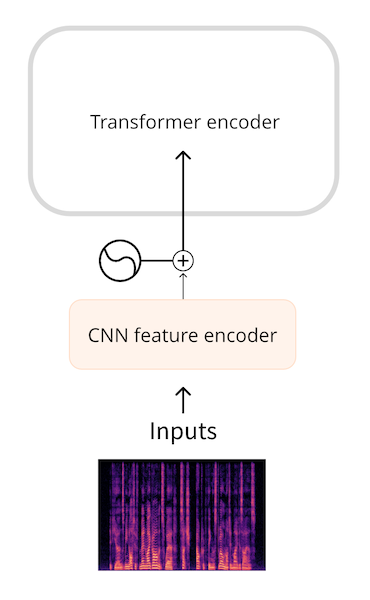

Because of this, raw audio waveforms are not usually the most efficient form of representing an audio input. By using a spectrogram, we get the same amount of information but in a more compressed form.

Models such as Whisper first convert the waveform into a log-mel spectrogram. Whisper always splits the audio into 30-second segments, and the log-mel spectrogram for each segment has shape (80, 3000) where 80 is the number of mel bins and 3000 is the sequence length. By converting to a log-mel spectrogram we’ve reduced the amount of input data, but more importantly, this is a much shorter sequence than the raw waveform. The log-mel spectrogram is then processed by a small CNN into a sequence of embeddings, which goes into the transformer as usual.

In both cases, waveform as well as spectrogram input, there is a small network in front of the transformer that converts the input into embeddings and then the transformer takes over to do its thing.

Model outputs

The transformer architecture outputs a sequence of hidden-state vectors, also known as the output embeddings. Our goal is to transform these vectors into a text or audio output.

Text output

The goal of an automatic speech recognition model is to predict a sequence of text tokens. This is done by adding a language modeling head — typically a single linear layer — followed by a softmax on top of the transformer’s output. This predicts the probabilities over the text tokens in the vocabulary.

Spectrogram output

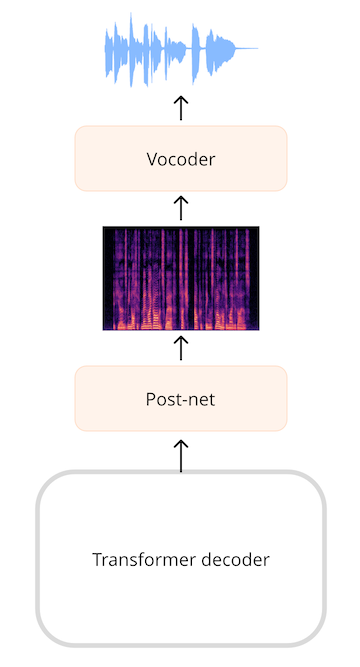

For models that generate audio, such as a text-to-speech (TTS) model, we’ll have to add layers that can produce an audio sequence. It’s very common to generate a spectrogram and then use an additional neural network, known as a vocoder, to turn this spectrogram into a waveform.

In the SpeechT5 TTS model, for example, the output from the transformer network is a sequence of 768-element vectors. A linear layer projects that sequence into a log-mel spectrogram. A so-called post-net, made up of additional linear and convolutional layers, refines the spectrogram by reducing noise. The vocoder then makes the final audio waveform.

💡 If you take an existing waveform and apply the Short-Time Fourier Transform or STFT, it is possible to perform the inverse operation, the ISTFT, to get the original waveform again. This works because the spectrogram created by the STFT contains both amplitude and phase information, and both are needed to reconstruct the waveform. However, audio models that generate their output as a spectrogram typically only predict the amplitude information, not the phase. To turn such a spectrogram into a waveform, we have to somehow estimate the phase information. That's what a vocoder does.

Waveform output

It’s also possible for models to directly output a waveform instead of a spectrogram as an intermediate step, but we currently don’t have any models in 🤗 Transformers that do this.

Conclusion

In summary: Most audio transformer models are more alike than different — they’re all built on the same transformer architecture and attention layers, although some models will only use the encoder portion of the transformer while others use both the encoder and decoder.

You’ve also seen how to get audio data into and out of transformer models. To perform the different audio tasks of ASR, TTS, and so on, we can simply swap out the layers that pre-process the inputs into embeddings, and swap out the layers that post-process the predicted embeddings into outputs, while the transformer backbone stays the same.

Next, let’s look at a few different ways these models can be trained to do automatic speech recognition.

Update on GitHub