# ML-Agents Toolkit Overview

**Table of Contents**

- [Running Example: Training NPC Behaviors](#running-example-training-npc-behaviors)

- [Key Components](#key-components)

- [Training Modes](#training-modes)

- [Built-in Training and Inference](#built-in-training-and-inference)

- [Cross-Platform Inference](#cross-platform-inference)

- [Custom Training and Inference](#custom-training-and-inference)

- [Flexible Training Scenarios](#flexible-training-scenarios)

- [Training Methods: Environment-agnostic](#training-methods-environment-agnostic)

- [A Quick Note on Reward Signals](#a-quick-note-on-reward-signals)

- [Deep Reinforcement Learning](#deep-reinforcement-learning)

- [Curiosity for Sparse-reward Environments](#curiosity-for-sparse-reward-environments)

- [RND for Sparse-reward Environments](#rnd-for-sparse-reward-environments)

- [Imitation Learning](#imitation-learning)

- [GAIL (Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning)](#gail-generative-adversarial-imitation-learning)

- [Behavioral Cloning (BC)](#behavioral-cloning-bc)

- [Recording Demonstrations](#recording-demonstrations)

- [Summary](#summary)

- [Training Methods: Environment-specific](#training-methods-environment-specific)

- [Training in Competitive Multi-Agent Environments with Self-Play](#training-in-competitive-multi-agent-environments-with-self-play)

- [Training in Cooperative Multi-Agent Environments with MA-POCA](#training-in-cooperative-multi-agent-environments-with-ma-poca)

- [Solving Complex Tasks using Curriculum Learning](#solving-complex-tasks-using-curriculum-learning)

- [Training Robust Agents using Environment Parameter Randomization](#training-robust-agents-using-environment-parameter-randomization)

- [Model Types](#model-types)

- [Learning from Vector Observations](#learning-from-vector-observations)

- [Learning from Cameras using Convolutional Neural Networks](#learning-from-cameras-using-convolutional-neural-networks)

- [Learning from Variable Length Observations using Attention](#learning-from-variable-length-observations-using-attention)

- [Memory-enhanced Agents using Recurrent Neural Networks](#memory-enhanced-agents-using-recurrent-neural-networks)

- [Additional Features](#additional-features)

- [Summary and Next Steps](#summary-and-next-steps)

**The Unity Machine Learning Agents Toolkit** (ML-Agents Toolkit) is an

open-source project that enables games and simulations to serve as environments

for training intelligent agents. Agents can be trained using reinforcement

learning, imitation learning, neuroevolution, or other machine learning methods

through a simple-to-use Python API. We also provide implementations (based on

PyTorch) of state-of-the-art algorithms to enable game developers and

hobbyists to easily train intelligent agents for 2D, 3D and VR/AR games. These

trained agents can be used for multiple purposes, including controlling NPC

behavior (in a variety of settings such as multi-agent and adversarial),

automated testing of game builds and evaluating different game design decisions

pre-release. The ML-Agents Toolkit is mutually beneficial for both game

developers and AI researchers as it provides a central platform where advances

in AI can be evaluated on Unity’s rich environments and then made accessible to

the wider research and game developer communities.

Depending on your background (i.e. researcher, game developer, hobbyist), you

may have very different questions on your mind at the moment. To make your

transition to the ML-Agents Toolkit easier, we provide several background pages

that include overviews and helpful resources on the

[Unity Engine](Background-Unity.md),

[machine learning](Background-Machine-Learning.md) and

[PyTorch](Background-PyTorch.md). We **strongly** recommend browsing the

relevant background pages if you're not familiar with a Unity scene, basic

machine learning concepts or have not previously heard of PyTorch.

The remainder of this page contains a deep dive into ML-Agents, its key

components, different training modes and scenarios. By the end of it, you should

have a good sense of _what_ the ML-Agents Toolkit allows you to do. The

subsequent documentation pages provide examples of _how_ to use ML-Agents. To

get started, watch this

[demo video of ML-Agents in action](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiQsmdwEGT8&feature=youtu.be).

## Running Example: Training NPC Behaviors

To help explain the material and terminology in this page, we'll use a

hypothetical, running example throughout. We will explore the problem of

training the behavior of a non-playable character (NPC) in a game. (An NPC is a

game character that is never controlled by a human player and its behavior is

pre-defined by the game developer.) More specifically, let's assume we're

building a multi-player, war-themed game in which players control the soldiers.

In this game, we have a single NPC who serves as a medic, finding and reviving

wounded players. Lastly, let us assume that there are two teams, each with five

players and one NPC medic.

The behavior of a medic is quite complex. It first needs to avoid getting

injured, which requires detecting when it is in danger and moving to a safe

location. Second, it needs to be aware of which of its team members are injured

and require assistance. In the case of multiple injuries, it needs to assess the

degree of injury and decide who to help first. Lastly, a good medic will always

place itself in a position where it can quickly help its team members. Factoring

in all of these traits means that at every instance, the medic needs to measure

several attributes of the environment (e.g. position of team members, position

of enemies, which of its team members are injured and to what degree) and then

decide on an action (e.g. hide from enemy fire, move to help one of its

members). Given the large number of settings of the environment and the large

number of actions that the medic can take, defining and implementing such

complex behaviors by hand is challenging and prone to errors.

With ML-Agents, it is possible to _train_ the behaviors of such NPCs (called

**Agents**) using a variety of methods. The basic idea is quite simple. We need

to define three entities at every moment of the game (called **environment**):

- **Observations** - what the medic perceives about the environment.

Observations can be numeric and/or visual. Numeric observations measure

attributes of the environment from the point of view of the agent. For our

medic this would be attributes of the battlefield that are visible to it. For

most interesting environments, an agent will require several continuous

numeric observations. Visual observations, on the other hand, are images

generated from the cameras attached to the agent and represent what the agent

is seeing at that point in time. It is common to confuse an agent's

observation with the environment (or game) **state**. The environment state

represents information about the entire scene containing all the game

characters. The agents observation, however, only contains information that

the agent is aware of and is typically a subset of the environment state. For

example, the medic observation cannot include information about an enemy in

hiding that the medic is unaware of.

- **Actions** - what actions the medic can take. Similar to observations,

actions can either be continuous or discrete depending on the complexity of

the environment and agent. In the case of the medic, if the environment is a

simple grid world where only their location matters, then a discrete action

taking on one of four values (north, south, east, west) suffices. However, if

the environment is more complex and the medic can move freely then using two

continuous actions (one for direction and another for speed) is more

appropriate.

- **Reward signals** - a scalar value indicating how well the medic is doing.

Note that the reward signal need not be provided at every moment, but only

when the medic performs an action that is good or bad. For example, it can

receive a large negative reward if it dies, a modest positive reward whenever

it revives a wounded team member, and a modest negative reward when a wounded

team member dies due to lack of assistance. Note that the reward signal is how

the objectives of the task are communicated to the agent, so they need to be

set up in a manner where maximizing reward generates the desired optimal

behavior.

After defining these three entities (the building blocks of a **reinforcement

learning task**), we can now _train_ the medic's behavior. This is achieved by

simulating the environment for many trials where the medic, over time, learns

what is the optimal action to take for every observation it measures by

maximizing its future reward. The key is that by learning the actions that

maximize its reward, the medic is learning the behaviors that make it a good

medic (i.e. one who saves the most number of lives). In **reinforcement

learning** terminology, the behavior that is learned is called a **policy**,

which is essentially a (optimal) mapping from observations to actions. Note that

the process of learning a policy through running simulations is called the

**training phase**, while playing the game with an NPC that is using its learned

policy is called the **inference phase**.

The ML-Agents Toolkit provides all the necessary tools for using Unity as the

simulation engine for learning the policies of different objects in a Unity

environment. In the next few sections, we discuss how the ML-Agents Toolkit

achieves this and what features it provides.

## Key Components

The ML-Agents Toolkit contains five high-level components:

- **Learning Environment** - which contains the Unity scene and all the game

characters. The Unity scene provides the environment in which agents observe,

act, and learn. How you set up the Unity scene to serve as a learning

environment really depends on your goal. You may be trying to solve a specific

reinforcement learning problem of limited scope, in which case you can use the

same scene for both training and for testing trained agents. Or, you may be

training agents to operate in a complex game or simulation. In this case, it

might be more efficient and practical to create a purpose-built training

scene. The ML-Agents Toolkit includes an ML-Agents Unity SDK

(`com.unity.ml-agents` package) that enables you to transform any Unity scene

into a learning environment by defining the agents and their behaviors.

- **Python Low-Level API** - which contains a low-level Python interface for

interacting and manipulating a learning environment. Note that, unlike the

Learning Environment, the Python API is not part of Unity, but lives outside

and communicates with Unity through the Communicator. This API is contained in

a dedicated `mlagents_envs` Python package and is used by the Python training

process to communicate with and control the Academy during training. However,

it can be used for other purposes as well. For example, you could use the API

to use Unity as the simulation engine for your own machine learning

algorithms. See [Python API](Python-LLAPI.md) for more information.

- **External Communicator** - which connects the Learning Environment with the

Python Low-Level API. It lives within the Learning Environment.

- **Python Trainers** which contains all the machine learning algorithms that

enable training agents. The algorithms are implemented in Python and are part

of their own `mlagents` Python package. The package exposes a single

command-line utility `mlagents-learn` that supports all the training methods

and options outlined in this document. The Python Trainers interface solely

with the Python Low-Level API.

- **Gym Wrapper** (not pictured). A common way in which machine learning

researchers interact with simulation environments is via a wrapper provided by

OpenAI called [gym](https://github.com/openai/gym). We provide a gym wrapper

in the `ml-agents-envs` package and [instructions](Python-Gym-API.md) for using

it with existing machine learning algorithms which utilize gym.

- **PettingZoo Wrapper** (not pictured) PettingZoo is python API for

interacting with multi-agent simulation environments that provides a

gym-like interface. We provide a PettingZoo wrapper for Unity ML-Agents

environments in the `ml-agents-envs` package and

[instructions](Python-PettingZoo-API.md) for using it with machine learning

algorithms.

_Simplified block diagram of ML-Agents._

The Learning Environment contains two Unity Components that help organize the

Unity scene:

- **Agents** - which is attached to a Unity GameObject (any character within a

scene) and handles generating its observations, performing the actions it

receives and assigning a reward (positive / negative) when appropriate. Each

Agent is linked to a Behavior.

- **Behavior** - defines specific attributes of the agent such as the number of

actions that agent can take. Each Behavior is uniquely identified by a

`Behavior Name` field. A Behavior can be thought as a function that receives

observations and rewards from the Agent and returns actions. A Behavior can be

of one of three types: Learning, Heuristic or Inference. A Learning Behavior

is one that is not, yet, defined but about to be trained. A Heuristic Behavior

is one that is defined by a hard-coded set of rules implemented in code. An

Inference Behavior is one that includes a trained Neural Network file. In

essence, after a Learning Behavior is trained, it becomes an Inference

Behavior.

Every Learning Environment will always have one Agent for every character in the

scene. While each Agent must be linked to a Behavior, it is possible for Agents

that have similar observations and actions to have the same Behavior. In our

sample game, we have two teams each with their own medic. Thus we will have two

Agents in our Learning Environment, one for each medic, but both of these medics

can have the same Behavior. This does not mean that at each instance they will

have identical observation and action _values_.

_Example block diagram of ML-Agents Toolkit for our sample game._

Note that in a single environment, there can be multiple Agents and multiple

Behaviors at the same time. For example, if we expanded our game to include tank

driver NPCs, then the Agent attached to those characters cannot share its

Behavior with the Agent linked to the medics (medics and drivers have different

actions). The Learning Environment through the Academy (not represented in the

diagram) ensures that all the Agents are in sync in addition to controlling

environment-wide settings.

Lastly, it is possible to exchange data between Unity and Python outside of the

machine learning loop through _Side Channels_. One example of using _Side

Channels_ is to exchange data with Python about _Environment Parameters_. The

following diagram illustrates the above.

## Training Modes

Given the flexibility of ML-Agents, there are a few ways in which training and

inference can proceed.

### Built-in Training and Inference

As mentioned previously, the ML-Agents Toolkit ships with several

implementations of state-of-the-art algorithms for training intelligent agents.

More specifically, during training, all the medics in the scene send their

observations to the Python API through the External Communicator. The Python API

processes these observations and sends back actions for each medic to take.

During training these actions are mostly exploratory to help the Python API

learn the best policy for each medic. Once training concludes, the learned

policy for each medic can be exported as a model file. Then during the inference

phase, the medics still continue to generate their observations, but instead of

being sent to the Python API, they will be fed into their (internal, embedded)

model to generate the _optimal_ action for each medic to take at every point in

time.

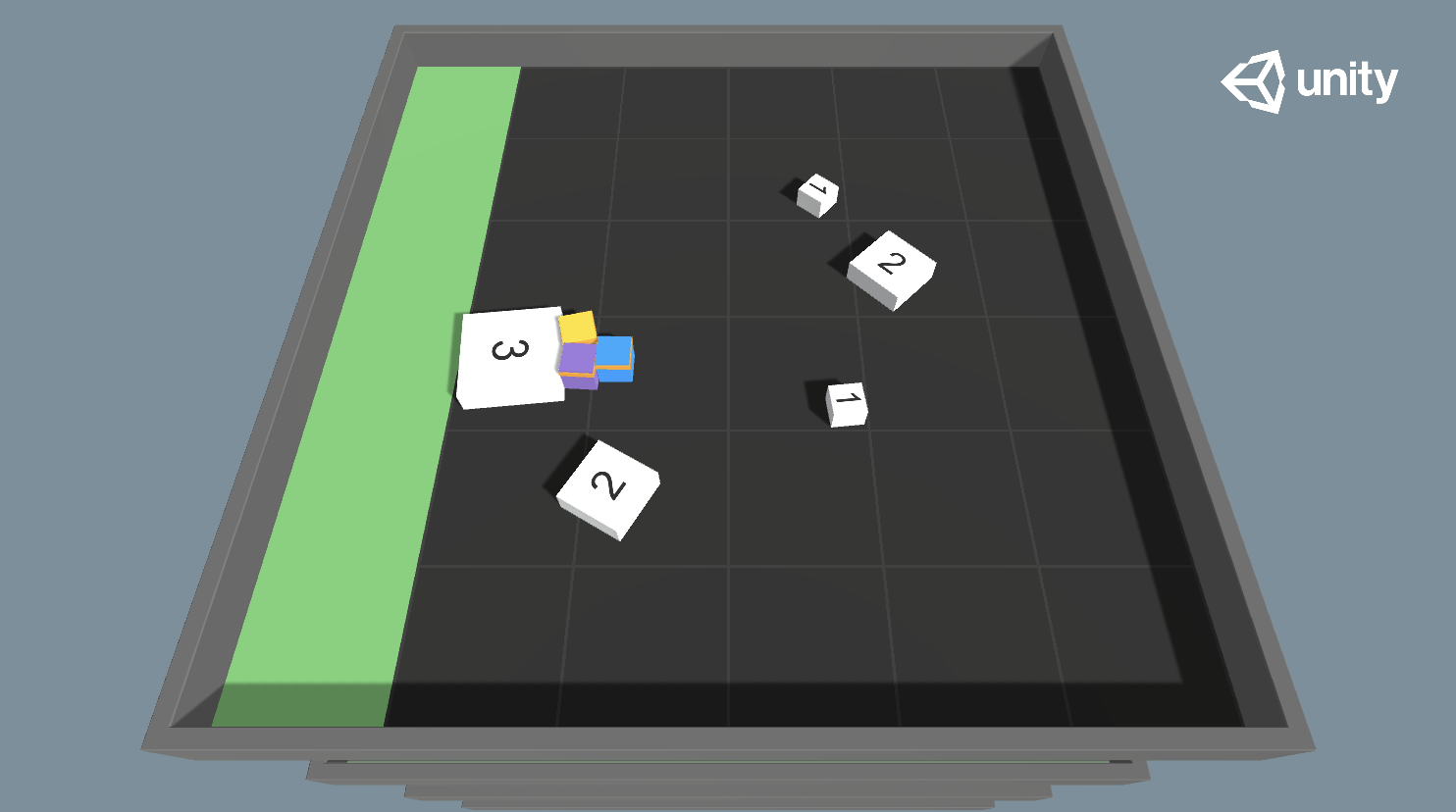

The [Getting Started Guide](Getting-Started.md) tutorial covers this training

mode with the **3D Balance Ball** sample environment.

#### Cross-Platform Inference

It is important to note that the ML-Agents Toolkit leverages the

[Unity Inference Engine](Unity-Inference-Engine.md) to run the models within a

Unity scene such that an agent can take the _optimal_ action at each step. Given

that the Unity Inference Engine support most platforms that Unity does, this

means that any model you train with the ML-Agents Toolkit can be embedded into

your Unity application that runs on any platform. See our

[dedicated blog post](https://blogs.unity3d.com/2019/03/01/unity-ml-agents-toolkit-v0-7-a-leap-towards-cross-platform-inference/)

for additional information.

### Custom Training and Inference

In the previous mode, the Agents were used for training to generate a PyTorch

model that the Agents can later use. However, any user of the ML-Agents Toolkit

can leverage their own algorithms for training. In this case, the behaviors of

all the Agents in the scene will be controlled within Python. You can even turn

your environment into a [gym.](Python-Gym-API.md)

We do not currently have a tutorial highlighting this mode, but you can learn

more about the Python API [here](Python-LLAPI.md).

## Flexible Training Scenarios

While the discussion so-far has mostly focused on training a single agent, with

ML-Agents, several training scenarios are possible. We are excited to see what

kinds of novel and fun environments the community creates. For those new to

training intelligent agents, below are a few examples that can serve as

inspiration:

- Single-Agent. A single agent, with its own reward signal. The traditional way

of training an agent. An example is any single-player game, such as Chicken.

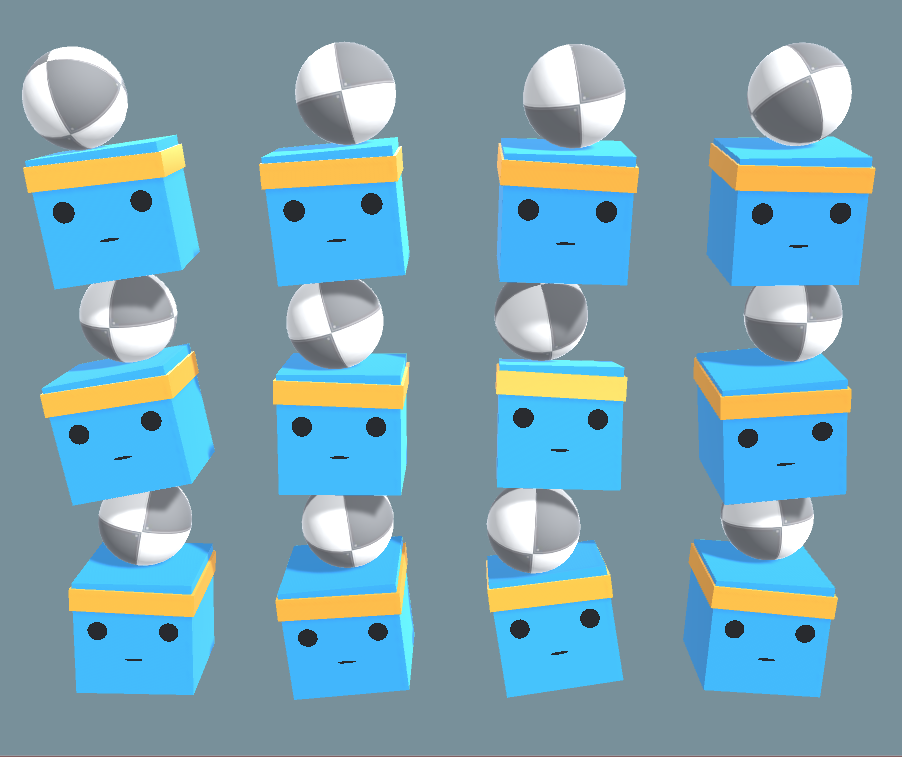

- Simultaneous Single-Agent. Multiple independent agents with independent reward

signals with same `Behavior Parameters`. A parallelized version of the

traditional training scenario, which can speed-up and stabilize the training

process. Helpful when you have multiple versions of the same character in an

environment who should learn similar behaviors. An example might be training a

dozen robot-arms to each open a door simultaneously.

- Adversarial Self-Play. Two interacting agents with inverse reward signals. In

two-player games, adversarial self-play can allow an agent to become

increasingly more skilled, while always having the perfectly matched opponent:

itself. This was the strategy employed when training AlphaGo, and more

recently used by OpenAI to train a human-beating 1-vs-1 Dota 2 agent.

- Cooperative Multi-Agent. Multiple interacting agents with a shared reward

signal with same or different `Behavior Parameters`. In this scenario, all

agents must work together to accomplish a task that cannot be done alone.

Examples include environments where each agent only has access to partial

information, which needs to be shared in order to accomplish the task or

collaboratively solve a puzzle.

- Competitive Multi-Agent. Multiple interacting agents with inverse reward

signals with same or different `Behavior Parameters`. In this scenario, agents

must compete with one another to either win a competition, or obtain some

limited set of resources. All team sports fall into this scenario.

- Ecosystem. Multiple interacting agents with independent reward signals with

same or different `Behavior Parameters`. This scenario can be thought of as

creating a small world in which animals with different goals all interact,

such as a savanna in which there might be zebras, elephants and giraffes, or

an autonomous driving simulation within an urban environment.

## Training Methods: Environment-agnostic

The remaining sections overview the various state-of-the-art machine learning

algorithms that are part of the ML-Agents Toolkit. If you aren't studying

machine and reinforcement learning as a subject and just want to train agents to

accomplish tasks, you can treat these algorithms as _black boxes_. There are a

few training-related parameters to adjust inside Unity as well as on the Python

training side, but you do not need in-depth knowledge of the algorithms

themselves to successfully create and train agents. Step-by-step procedures for

running the training process are provided in the

[Training ML-Agents](Training-ML-Agents.md) page.

This section specifically focuses on the training methods that are available

regardless of the specifics of your learning environment.

#### A Quick Note on Reward Signals

In this section we introduce the concepts of _intrinsic_ and _extrinsic_

rewards, which helps explain some of the training methods.

In reinforcement learning, the end goal for the Agent is to discover a behavior

(a Policy) that maximizes a reward. You will need to provide the agent one or

more reward signals to use during training. Typically, a reward is defined by

your environment, and corresponds to reaching some goal. These are what we refer

to as _extrinsic_ rewards, as they are defined external of the learning

algorithm.

Rewards, however, can be defined outside of the environment as well, to

encourage the agent to behave in certain ways, or to aid the learning of the

true extrinsic reward. We refer to these rewards as _intrinsic_ reward signals.

The total reward that the agent will learn to maximize can be a mix of extrinsic

and intrinsic reward signals.

The ML-Agents Toolkit allows reward signals to be defined in a modular way, and

we provide four reward signals that can the mixed and matched to help shape

your agent's behavior:

- `extrinsic`: represents the rewards defined in your environment, and is

enabled by default

- `gail`: represents an intrinsic reward signal that is defined by GAIL (see

below)

- `curiosity`: represents an intrinsic reward signal that encourages exploration

in sparse-reward environments that is defined by the Curiosity module (see

below).

- `rnd`: represents an intrinsic reward signal that encourages exploration

in sparse-reward environments that is defined by the Curiosity module (see

below).

### Deep Reinforcement Learning

ML-Agents provide an implementation of two reinforcement learning algorithms:

- [Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)](https://blog.openai.com/openai-baselines-ppo/)

- [Soft Actor-Critic (SAC)](https://bair.berkeley.edu/blog/2018/12/14/sac/)

The default algorithm is PPO. This is a method that has been shown to be more

general purpose and stable than many other RL algorithms.

In contrast with PPO, SAC is _off-policy_, which means it can learn from

experiences collected at any time during the past. As experiences are collected,

they are placed in an experience replay buffer and randomly drawn during

training. This makes SAC significantly more sample-efficient, often requiring

5-10 times less samples to learn the same task as PPO. However, SAC tends to

require more model updates. SAC is a good choice for heavier or slower

environments (about 0.1 seconds per step or more). SAC is also a "maximum

entropy" algorithm, and enables exploration in an intrinsic way. Read more about

maximum entropy RL

[here](https://bair.berkeley.edu/blog/2017/10/06/soft-q-learning/).

#### Curiosity for Sparse-reward Environments

In environments where the agent receives rare or infrequent rewards (i.e.

sparse-reward), an agent may never receive a reward signal on which to bootstrap

its training process. This is a scenario where the use of an intrinsic reward

signals can be valuable. Curiosity is one such signal which can help the agent

explore when extrinsic rewards are sparse.

The `curiosity` Reward Signal enables the Intrinsic Curiosity Module. This is an

implementation of the approach described in

[Curiosity-driven Exploration by Self-supervised Prediction](https://pathak22.github.io/noreward-rl/)

by Pathak, et al. It trains two networks:

- an inverse model, which takes the current and next observation of the agent,

encodes them, and uses the encoding to predict the action that was taken

between the observations

- a forward model, which takes the encoded current observation and action, and

predicts the next encoded observation.

The loss of the forward model (the difference between the predicted and actual

encoded observations) is used as the intrinsic reward, so the more surprised the

model is, the larger the reward will be.

For more information, see our dedicated

[blog post on the Curiosity module](https://blogs.unity3d.com/2018/06/26/solving-sparse-reward-tasks-with-curiosity/).

#### RND for Sparse-reward Environments

Similarly to Curiosity, Random Network Distillation (RND) is useful in sparse or rare

reward environments as it helps the Agent explore. The RND Module is implemented following

the paper [Exploration by Random Network Distillation](https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.12894).

RND uses two networks:

- The first is a network with fixed random weights that takes observations as inputs and

generates an encoding

- The second is a network with similar architecture that is trained to predict the

outputs of the first network and uses the observations the Agent collects as training data.

The loss (the squared difference between the predicted and actual encoded observations)

of the trained model is used as intrinsic reward. The more an Agent visits a state, the

more accurate the predictions and the lower the rewards which encourages the Agent to

explore new states with higher prediction errors.

### Imitation Learning

It is often more intuitive to simply demonstrate the behavior we want an agent

to perform, rather than attempting to have it learn via trial-and-error methods.

For example, instead of indirectly training a medic with the help of a reward

function, we can give the medic real world examples of observations from the

game and actions from a game controller to guide the medic's behavior. Imitation

Learning uses pairs of observations and actions from a demonstration to learn a

policy. See this [video demo](https://youtu.be/kpb8ZkMBFYs) of imitation

learning .

Imitation learning can either be used alone or in conjunction with reinforcement

learning. If used alone it can provide a mechanism for learning a specific type

of behavior (i.e. a specific style of solving the task). If used in conjunction

with reinforcement learning it can dramatically reduce the time the agent takes

to solve the environment. This can be especially pronounced in sparse-reward

environments. For instance, on the

[Pyramids environment](Learning-Environment-Examples.md#pyramids), using 6

episodes of demonstrations can reduce training steps by more than 4 times. See

Behavioral Cloning + GAIL + Curiosity + RL below.

The ML-Agents Toolkit provides a way to learn directly from demonstrations, as

well as use them to help speed up reward-based training (RL). We include two

algorithms called Behavioral Cloning (BC) and Generative Adversarial Imitation

Learning (GAIL). In most scenarios, you can combine these two features:

- If you want to help your agents learn (especially with environments that have

sparse rewards) using pre-recorded demonstrations, you can generally enable

both GAIL and Behavioral Cloning at low strengths in addition to having an

extrinsic reward. An example of this is provided for the PushBlock example

environment in `config/imitation/PushBlock.yaml`.

- If you want to train purely from demonstrations with GAIL and BC _without_ an

extrinsic reward signal, please see the CrawlerStatic example environment under

in `config/imitation/CrawlerStatic.yaml`.

***Note:*** GAIL introduces a [_survivor bias_](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1809.02925.pdf)

to the learning process. That is, by giving positive rewards based on similarity

to the expert, the agent is incentivized to remain alive for as long as possible.

This can directly conflict with goal-oriented tasks like our PushBlock or Pyramids

example environments where an agent must reach a goal state thus ending the

episode as quickly as possible. In these cases, we strongly recommend that you

use a low strength GAIL reward signal and a sparse extrinisic signal when

the agent achieves the task. This way, the GAIL reward signal will guide the

agent until it discovers the extrnisic signal and will not overpower it. If the

agent appears to be ignoring the extrinsic reward signal, you should reduce

the strength of GAIL.

#### GAIL (Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning)

GAIL, or

[Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning](https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.03476),

uses an adversarial approach to reward your Agent for behaving similar to a set

of demonstrations. GAIL can be used with or without environment rewards, and

works well when there are a limited number of demonstrations. In this framework,

a second neural network, the discriminator, is taught to distinguish whether an

observation/action is from a demonstration or produced by the agent. This

discriminator can then examine a new observation/action and provide it a reward

based on how close it believes this new observation/action is to the provided

demonstrations.

At each training step, the agent tries to learn how to maximize this reward.

Then, the discriminator is trained to better distinguish between demonstrations

and agent state/actions. In this way, while the agent gets better and better at

mimicking the demonstrations, the discriminator keeps getting stricter and

stricter and the agent must try harder to "fool" it.

This approach learns a _policy_ that produces states and actions similar to the

demonstrations, requiring fewer demonstrations than direct cloning of the

actions. In addition to learning purely from demonstrations, the GAIL reward

signal can be mixed with an extrinsic reward signal to guide the learning

process.

#### Behavioral Cloning (BC)

BC trains the Agent's policy to exactly mimic the actions shown in a set of

demonstrations. The BC feature can be enabled on the PPO or SAC trainers. As BC

cannot generalize past the examples shown in the demonstrations, BC tends to

work best when there exists demonstrations for nearly all of the states that the

agent can experience, or in conjunction with GAIL and/or an extrinsic reward.

#### Recording Demonstrations

Demonstrations of agent behavior can be recorded from the Unity Editor or build,

and saved as assets. These demonstrations contain information on the

observations, actions, and rewards for a given agent during the recording

session. They can be managed in the Editor, as well as used for training with BC

and GAIL. See the

[Designing Agents](Learning-Environment-Design-Agents.md#recording-demonstrations)

page for more information on how to record demonstrations for your agent.

### Summary

To summarize, we provide 3 training methods: BC, GAIL and RL (PPO or SAC) that

can be used independently or together:

- BC can be used on its own or as a pre-training step before GAIL and/or RL

- GAIL can be used with or without extrinsic rewards

- RL can be used on its own (either PPO or SAC) or in conjunction with BC and/or

GAIL.

Leveraging either BC or GAIL requires recording demonstrations to be provided as

input to the training algorithms.

## Training Methods: Environment-specific

In addition to the three environment-agnostic training methods introduced in the

previous section, the ML-Agents Toolkit provides additional methods that can aid

in training behaviors for specific types of environments.

### Training in Competitive Multi-Agent Environments with Self-Play

ML-Agents provides the functionality to train both symmetric and asymmetric

adversarial games with

[Self-Play](https://openai.com/blog/competitive-self-play/). A symmetric game is

one in which opposing agents are equal in form, function and objective. Examples

of symmetric games are our Tennis and Soccer example environments. In

reinforcement learning, this means both agents have the same observation and

actions and learn from the same reward function and so _they can share the

same policy_. In asymmetric games, this is not the case. An example of an

asymmetric games are Hide and Seek. Agents in these types of games do not always

have the same observation or actions and so sharing policy networks is not

necessarily ideal.

With self-play, an agent learns in adversarial games by competing against fixed,

past versions of its opponent (which could be itself as in symmetric games) to

provide a more stable, stationary learning environment. This is compared to

competing against the current, best opponent in every episode, which is

constantly changing (because it's learning).

Self-play can be used with our implementations of both Proximal Policy

Optimization (PPO) and Soft Actor-Critic (SAC). However, from the perspective of

an individual agent, these scenarios appear to have non-stationary dynamics

because the opponent is often changing. This can cause significant issues in the

experience replay mechanism used by SAC. Thus, we recommend that users use PPO.

For further reading on this issue in particular, see the paper

[Stabilising Experience Replay for Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1702.08887.pdf).

See our

[Designing Agents](Learning-Environment-Design-Agents.md#defining-teams-for-multi-agent-scenarios)

page for more information on setting up teams in your Unity scene. Also, read

our

[blog post on self-play](https://blogs.unity3d.com/2020/02/28/training-intelligent-adversaries-using-self-play-with-ml-agents/)

for additional information. Additionally, check [ELO Rating System](ELO-Rating-System.md) the method we use to calculate

the relative skill level between two players.

### Training In Cooperative Multi-Agent Environments with MA-POCA

ML-Agents provides the functionality for training cooperative behaviors - i.e.,

groups of agents working towards a common goal, where the success of the individual

is linked to the success of the whole group. In such a scenario, agents typically receive

rewards as a group. For instance, if a team of agents wins a game against an opposing

team, everyone is rewarded - even agents who did not directly contribute to the win. This

makes learning what to do as an individual difficult - you may get a win

for doing nothing, and a loss for doing your best.

In ML-Agents, we provide MA-POCA (MultiAgent POsthumous Credit Assignment), which

is a novel multi-agent trainer that trains a _centralized critic_, a neural network

that acts as a "coach" for a whole group of agents. You can then give rewards to the team

as a whole, and the agents will learn how best to contribute to achieving that reward.

Agents can _also_ be given rewards individually, and the team will work together to help the

individual achieve those goals. During an episode, agents can be added or removed from the group,

such as when agents spawn or die in a game. If agents are removed mid-episode (e.g., if teammates die

or are removed from the game), they will still learn whether their actions contributed

to the team winning later, enabling agents to take group-beneficial actions even if

they result in the individual being removed from the game (i.e., self-sacrifice).

MA-POCA can also be combined with self-play to train teams of agents to play against each other.

To learn more about enabling cooperative behaviors for agents in an ML-Agents environment,

check out [this page](Learning-Environment-Design-Agents.md#groups-for-cooperative-scenarios).

To learn more about MA-POCA, please see our paper

[On the Use and Misuse of Absorbing States in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning](https://arxiv.org/pdf/2111.05992.pdf).

For further reading, MA-POCA builds on previous work in multi-agent cooperative learning

([Lowe et al.](https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.02275), [Foerster et al.](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1705.08926.pdf),

among others) to enable the above use-cases.

### Solving Complex Tasks using Curriculum Learning

Curriculum learning is a way of training a machine learning model where more

difficult aspects of a problem are gradually introduced in such a way that the

model is always optimally challenged. This idea has been around for a long time,

and it is how we humans typically learn. If you imagine any childhood primary

school education, there is an ordering of classes and topics. Arithmetic is

taught before algebra, for example. Likewise, algebra is taught before calculus.

The skills and knowledge learned in the earlier subjects provide a scaffolding

for later lessons. The same principle can be applied to machine learning, where

training on easier tasks can provide a scaffolding for harder tasks in the

future.

Imagine training the medic to scale a wall to arrive at a wounded team

member. The starting point when training a medic to accomplish this task will be

a random policy. That starting policy will have the medic running in circles,

and will likely never, or very rarely scale the wall properly to revive their

team member (and achieve the reward). If we start with a simpler task, such as

moving toward an unobstructed team member, then the medic can easily learn to

accomplish the task. From there, we can slowly add to the difficulty of the task

by increasing the size of the wall until the medic can complete the initially

near-impossible task of scaling the wall. We have included an environment to

demonstrate this with ML-Agents, called

[Wall Jump](Learning-Environment-Examples.md#wall-jump).

_Demonstration of a hypothetical curriculum training scenario in which a

progressively taller wall obstructs the path to the goal._

_[**Note**: The example provided above is for instructional purposes, and was

based on an early version of the

[Wall Jump example environment](Learning-Environment-Examples.md). As such, it

is not possible to directly replicate the results here using that environment.]_

The ML-Agents Toolkit supports modifying custom environment parameters during

the training process to aid in learning. This allows elements of the environment

related to difficulty or complexity to be dynamically adjusted based on training

progress. The [Training ML-Agents](Training-ML-Agents.md#curriculum-learning)

page has more information on defining training curriculums.

### Training Robust Agents using Environment Parameter Randomization

An agent trained on a specific environment, may be unable to generalize to any

tweaks or variations in the environment (in machine learning this is referred to

as overfitting). This becomes problematic in cases where environments are

instantiated with varying objects or properties. One mechanism to alleviate this

and train more robust agents that can generalize to unseen variations of the

environment is to expose them to these variations during training. Similar to

Curriculum Learning, where environments become more difficult as the agent

learns, the ML-Agents Toolkit provides a way to randomly sample parameters of

the environment during training. We refer to this approach as **Environment

Parameter Randomization**. For those familiar with Reinforcement Learning

research, this approach is based on the concept of

[Domain Randomization](https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.06907). By using

[parameter randomization during training](Training-ML-Agents.md#environment-parameter-randomization),

the agent can be better suited to adapt (with higher performance) to future

unseen variations of the environment.

| Ball scale of 0.5 | Ball scale of 4 |

| :--------------------------: | :------------------------: |

|  |  |

_Example of variations of the 3D Ball environment. The environment parameters

are `gravity`, `ball_mass` and `ball_scale`._

## Model Types

Regardless of the training method deployed, there are a few model types that

users can train using the ML-Agents Toolkit. This is due to the flexibility in

defining agent observations, which include vector, ray cast and visual

observations. You can learn more about how to instrument an agent's observation

in the [Designing Agents](Learning-Environment-Design-Agents.md) guide.

### Learning from Vector Observations

Whether an agent's observations are ray cast or vector, the ML-Agents Toolkit

provides a fully connected neural network model to learn from those

observations. At training time you can configure different aspects of this model

such as the number of hidden units and number of layers.

### Learning from Cameras using Convolutional Neural Networks

Unlike other platforms, where the agent’s observation might be limited to a

single vector or image, the ML-Agents Toolkit allows multiple cameras to be used

for observations per agent. This enables agents to learn to integrate

information from multiple visual streams. This can be helpful in several

scenarios such as training a self-driving car which requires multiple cameras

with different viewpoints, or a navigational agent which might need to integrate

aerial and first-person visuals. You can learn more about adding visual

observations to an agent

[here](Learning-Environment-Design-Agents.md#multiple-visual-observations).

When visual observations are utilized, the ML-Agents Toolkit leverages

convolutional neural networks (CNN) to learn from the input images. We offer

three network architectures:

- a simple encoder which consists of two convolutional layers

- the implementation proposed by

[Mnih et al.](https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14236), consisting of

three convolutional layers,

- the [IMPALA Resnet](https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.01561) consisting of three

stacked layers, each with two residual blocks, making a much larger network

than the other two.

The choice of the architecture depends on the visual complexity of the scene and

the available computational resources.

### Learning from Variable Length Observations using Attention

Using the ML-Agents Toolkit, it is possible to have agents learn from a

varying number of inputs. To do so, each agent can keep track of a buffer

of vector observations. At each step, the agent will go through all the

elements in the buffer and extract information but the elements

in the buffer can change at every step.

This can be useful in scenarios in which the agents must keep track of

a varying number of elements throughout the episode. For example in a game

where an agent must learn to avoid projectiles, but the projectiles can vary in

numbers.

You can learn more about variable length observations

[here](Learning-Environment-Design-Agents.md#variable-length-observations).

When variable length observations are utilized, the ML-Agents Toolkit

leverages attention networks to learn from a varying number of entities.

Agents using attention will ignore entities that are deemed not relevant

and pay special attention to entities relevant to the current situation

based on context.

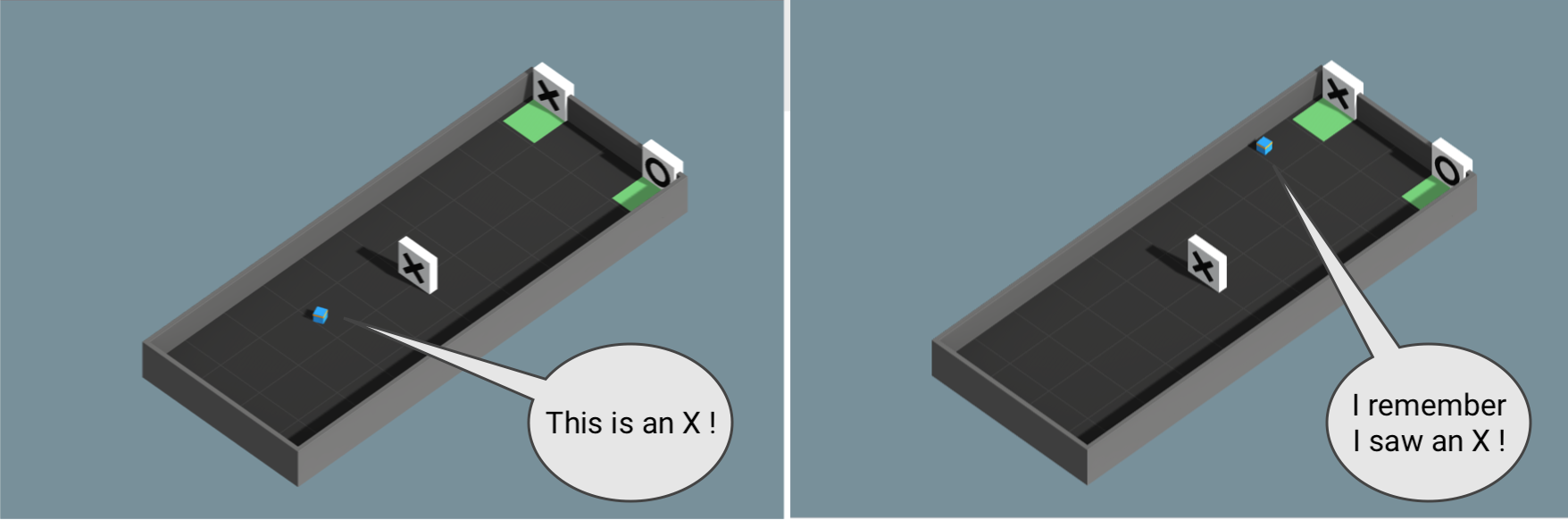

### Memory-enhanced Agents using Recurrent Neural Networks

Have you ever entered a room to get something and immediately forgot what you

were looking for? Don't let that happen to your agents.

In some scenarios, agents must learn to remember the past in order to take the

best decision. When an agent only has partial observability of the environment,

keeping track of past observations can help the agent learn. Deciding what the

agents should remember in order to solve a task is not easy to do by hand, but

our training algorithms can learn to keep track of what is important to remember

with [LSTM](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_short-term_memory).

## Additional Features

Beyond the flexible training scenarios available, the ML-Agents Toolkit includes

additional features which improve the flexibility and interpretability of the

training process.

- **Concurrent Unity Instances** - We enable developers to run concurrent,

parallel instances of the Unity executable during training. For certain

scenarios, this should speed up training. Check out our dedicated page on

[creating a Unity executable](Learning-Environment-Executable.md) and the

[Training ML-Agents](Training-ML-Agents.md#training-using-concurrent-unity-instances)

page for instructions on how to set the number of concurrent instances.

- **Recording Statistics from Unity** - We enable developers to

[record statistics](Learning-Environment-Design.md#recording-statistics) from

within their Unity environments. These statistics are aggregated and generated

during the training process.

- **Custom Side Channels** - We enable developers to

[create custom side channels](Custom-SideChannels.md) to manage data transfer

between Unity and Python that is unique to their training workflow and/or

environment.

- **Custom Samplers** - We enable developers to

[create custom sampling methods](Training-ML-Agents.md#defining-a-new-sampler-type)

for Environment Parameter Randomization. This enables users to customize this

training method for their particular environment.

## Summary and Next Steps

To briefly summarize: The ML-Agents Toolkit enables games and simulations built

in Unity to serve as the platform for training intelligent agents. It is

designed to enable a large variety of training modes and scenarios and comes

packed with several features to enable researchers and developers to leverage

(and enhance) machine learning within Unity.

In terms of next steps:

- For a walkthrough of running ML-Agents with a simple scene, check out the

[Getting Started](Getting-Started.md) guide.

- For a "Hello World" introduction to creating your own Learning Environment,

check out the

[Making a New Learning Environment](Learning-Environment-Create-New.md) page.

- For an overview on the more complex example environments that are provided in

this toolkit, check out the

[Example Environments](Learning-Environment-Examples.md) page.

- For more information on the various training options available, check out the

[Training ML-Agents](Training-ML-Agents.md) page.